Our Mission

The Fair Fight Initiative champions a just and balanced criminal legal system that focuses on rehabilitating rather than punishing children.

Juvenile Justice

Juvenile JusticeThe Fair Fight Initiative’s recent work in Louisiana—fighting against the placement of adolescent males onto a cellblock formerly used as the state’s death row in Angola—has led to profound questions about the purpose of the juvenile justice system. Louisiana’s response to antisocial and alleged violent behaviors by adolescent males, almost all Black, has been punitive. Days of solitary confinement, excessive use of physical restraints like handcuffs, shackles, and pepper spray, and the imposition of adult prison practices have become the norm in Louisiana. The question is: Does this make us safer?

Before 1900, most states treated young people who were accused of crime the same as adults. In 1899, the first juvenile court, designed to treat children differently than adults and recognizing that, was established in Chicago, Illinois. Now every state in the country has separate juvenile justice systems that handle adolescents accused of crimes differently.

One key distinction: People in the juvenile justice system who are culpable for committing a crime are not convicted of anything. They are adjudicated delinquent, which means the state cannot legally punish them. Adults who commit a crime, once convicted, can legally be punished. Once found delinquent in the juvenile justice system, adolescents are entitled to education, counseling, and other treatment geared toward rehabilitation.

One key distinction: People in the juvenile justice system who are culpable for committing a crime are not convicted of anything. They are adjudicated delinquent, which means the state cannot legally punish them. Adults who commit a crime, once convicted, can legally be punished. Once found delinquent in the juvenile justice system, adolescents are entitled to education, counseling, and other treatment geared toward rehabilitation.

This is not to say that the law is always followed and enforced. Like much of America’s legal system, juvenile justice systems across the country treat Black adolescents much harsher than white kids. Our work in Louisiana found that, of the 80 or so adolescent males sent to Angola, almost all of them were Black. Nationally, even though adolescents self-report criminal behavior at nearly the same rate, Black youth are 2.3 times as likely to be arrested as white kids. These disparities continue at every stage of the juvenile justice system, with the worst treatment option—incarceration—disproportionately used on Black adolescents after being adjudicated delinquent.

This matters because what we have learned over the past twenty years or so is that removing adolescents from their homes and community for law violations is the least effective—and most expensive—way to handle juvenile crime. The more we have learned about brain development, the clearer it is that adolescence is an incredibly important phase of development. The simple definition of adolescence is the stage of development that occurs between childhood and adulthood. Although the age range varies, adolescence is generally considered to encompass the teenage years, typically starting around the onset of puberty and extending into the early 20s. The things that happen to a person going through adolescence are shared, no matter the culture or region.

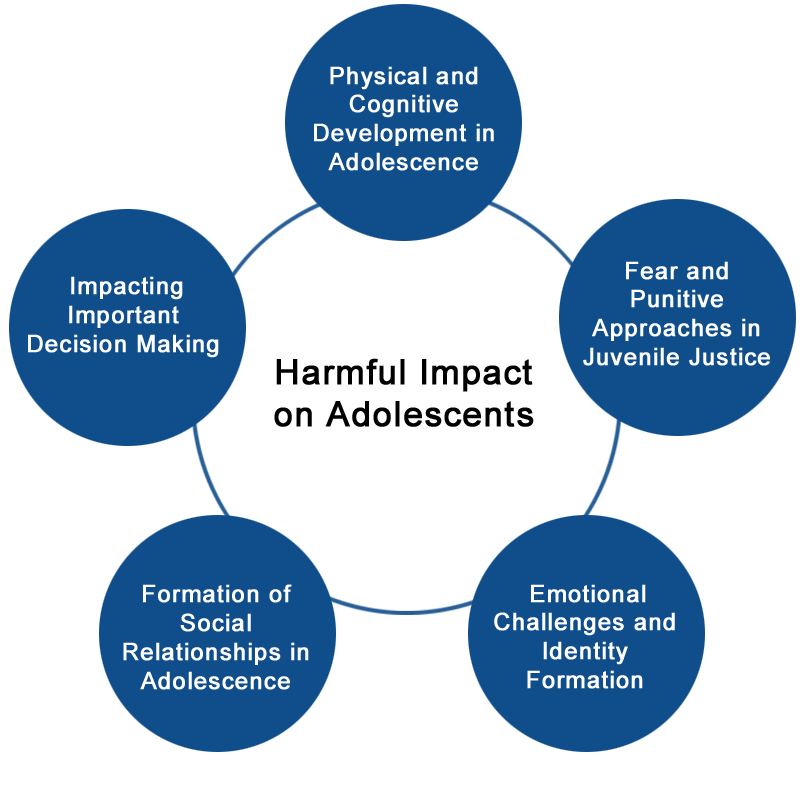

Key aspects of adolescence include physical growth and cognitive development, including emotional and social development. The physical and cognitive growth that happens in adolescence are key to understanding why punitive approaches to juvenile justice are both readily adopted and yet fail to deliver better outcomes. Readily adopted because the bigger kids get, the more likely our juvenile justice system fears them and respond by punishing them as adult. Indeed, as recently as 1944 one state used the death penalty on a 14 year old Black child.

Punitive approaches to juvenile justice fail us because the adolescent brain undergoes significant cognitive development that include improvements in abstract thinking, problem-solving abilities, and decision-making. Anyone who has ever raised teenagers knows that experience heightened emotions and often have issues related to identity, self-esteem, and independence. Adolescence is a time when humans form new social relationships, both within and outside of their families, and begin to explore their own values and beliefs. Removing a young person from their home and community and placing them in an institution with other adolescents who are adjudicated delinquent creates peer pressure to commit more crime, not less.

Punitive approaches to juvenile justice fail us because the adolescent brain undergoes significant cognitive development that include improvements in abstract thinking, problem-solving abilities, and decision-making. Anyone who has ever raised teenagers knows that experience heightened emotions and often have issues related to identity, self-esteem, and independence. Adolescence is a time when humans form new social relationships, both within and outside of their families, and begin to explore their own values and beliefs. Removing a young person from their home and community and placing them in an institution with other adolescents who are adjudicated delinquent creates peer pressure to commit more crime, not less.

Fortunately, punitive approaches like incarceration have been reduced dramatically over the past 20 years in America. According to a recent report by the Sentencing Project, the number of youth locked up has declined by 77% from 2000 and 2020. This is really good news and its made better by dramatic drops in the juvenile crime rate. According to that same report, since 1996 the juvenile arrest rate has dropped even more—by more than 80%.

Despite its ineffectiveness and harmful impact on adolescents—a harm disproportionally inflicted on Black males—many states continue to overuse incarceration in their juvenile justice system. This is expensive—one report estimated that it costs over $150,000 a year to incarcerate a single child in Louisiana, compared with a little more than $11,000 to put them in college for a year —and counterproductive to the goals of the juvenile justice system. In order to create safer communities, we must continue the work to respond to juvenile crime with community-based alternatives to incarceration.

“Every child born in our nation deserves to be valued, and if they encounter legal troubles, successful rehabilitation is achievable. The Fair Fight Initiative champions a just and balanced criminal legal system that focuses on rehabilitating rather than punishing children. Through generous donations, the Fair Fight Initiative offers support to victims and their families, facilitating litigation for those who have been wronged or harmed by our broken system of justice. We warmly invite you to contribute a tax-deductible donation to bolster our cause. Fair Fight extends its deepest gratitude for your consideration, kindness, and generous support.

Featured in The Media