Unwarranted

How East Baton Rouge Parish’s Warrant Practices Make Us Less Safe

August 2022 – Download Full PDF Here

At a Glance

The Problem:

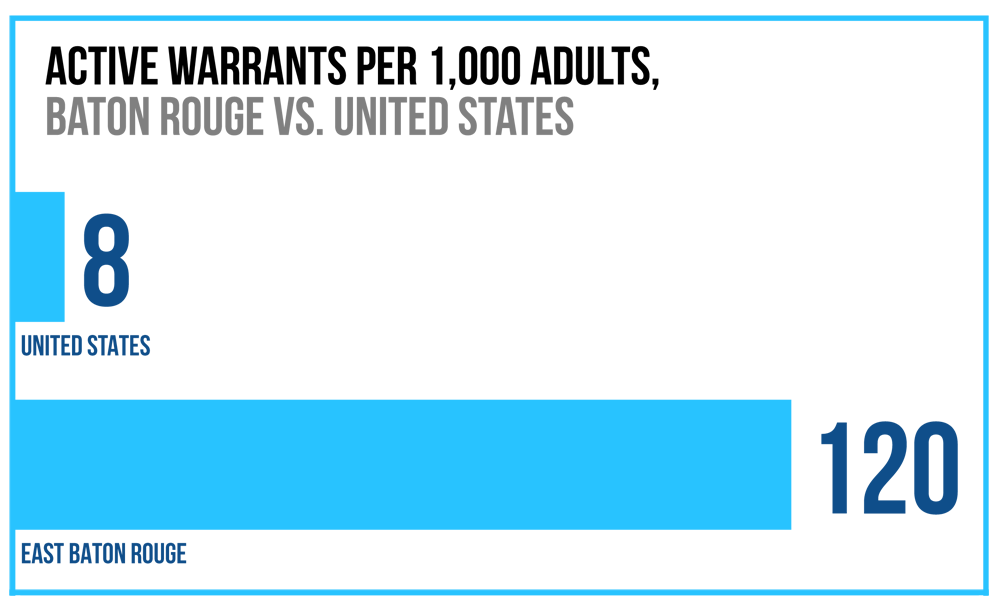

- East Baton Rouge Parish (“Baton Rouge,” or “Parish”) has too many active warrants. The number of active warrants per capita is 15 times the national average.

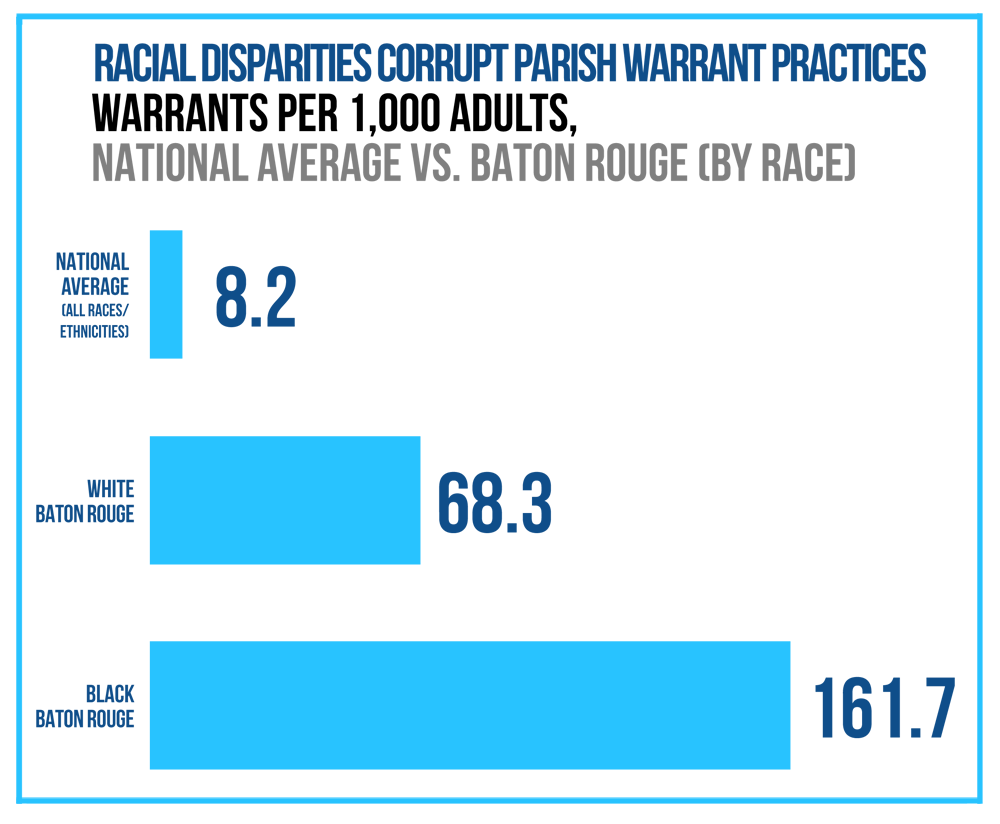

- Racial disparities plague the system. Black people in the parish are 2.4 times more likely to have a warrant than white people.

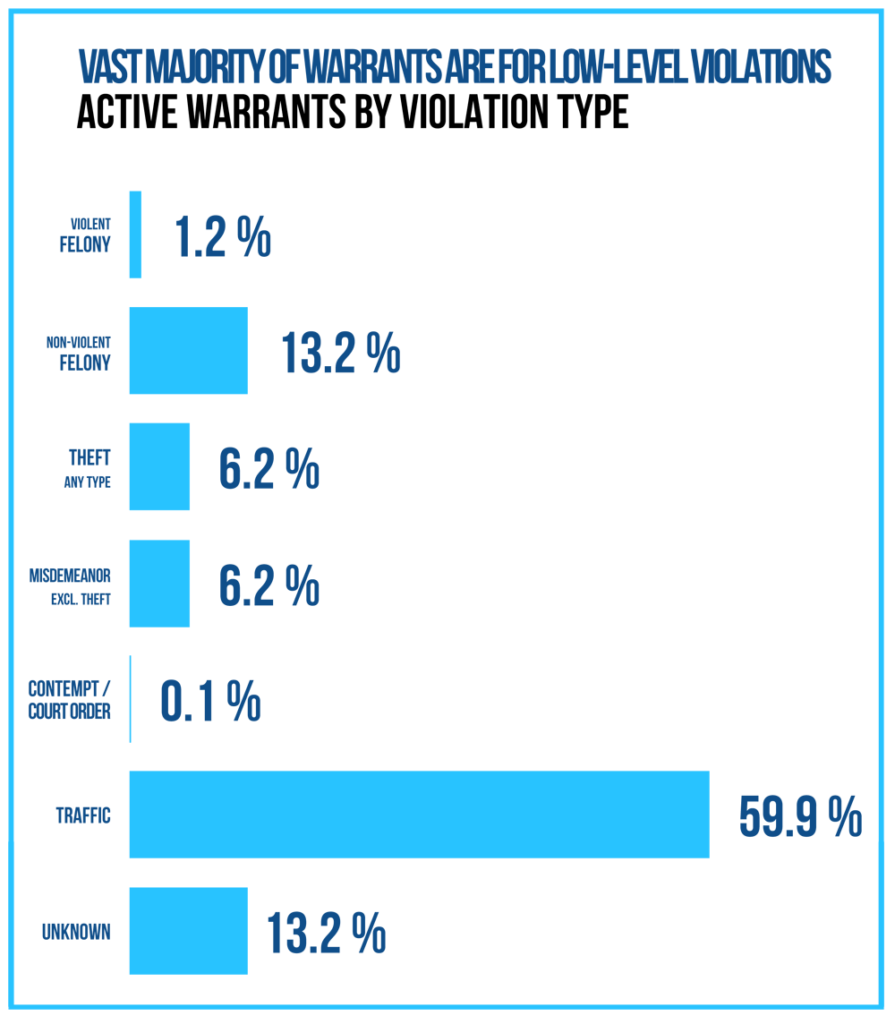

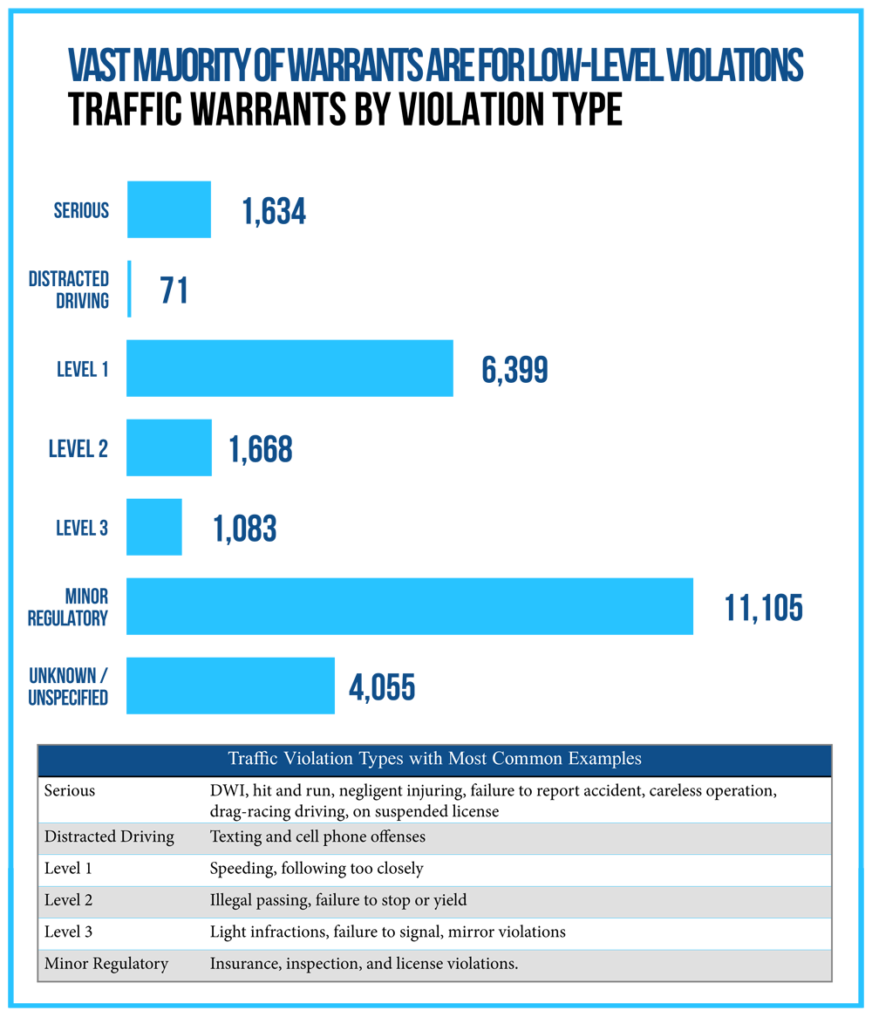

- The vast majority of warrants are for violations that are not serious and do not result in jail time. Only 1.2 percent of active warrants are for violent felonies.

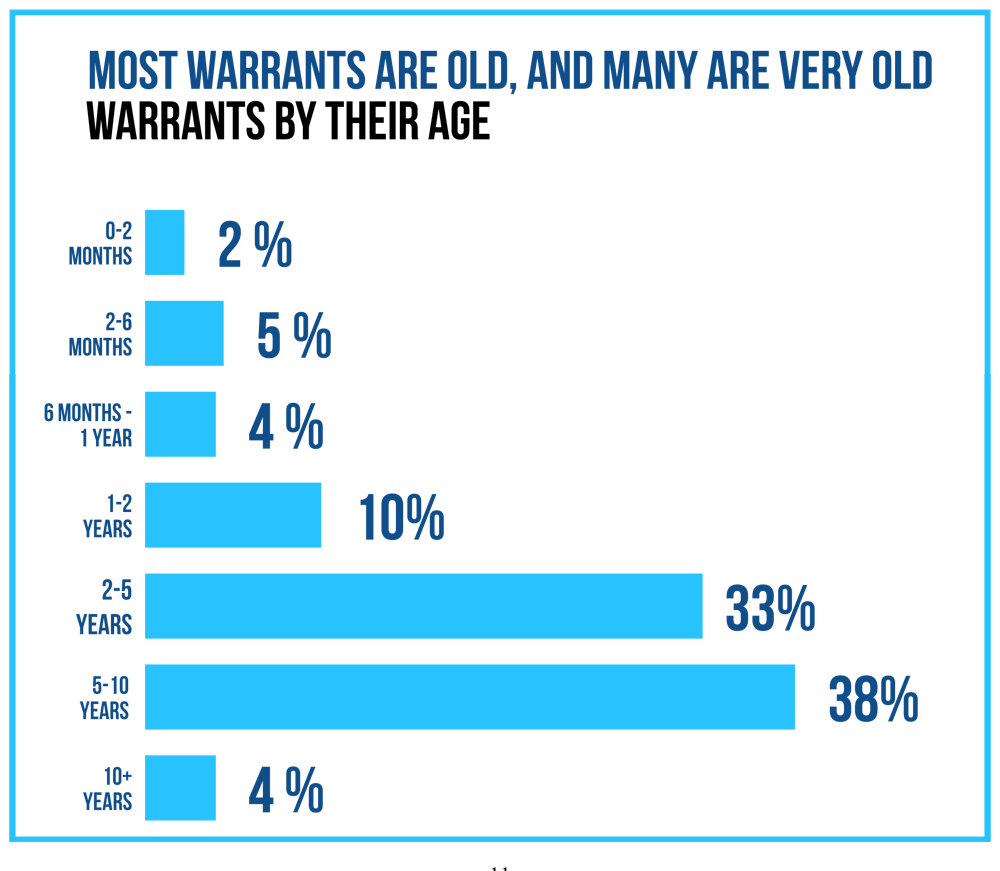

- Warrants in Baton Rouge are extremely old. 89 percent are older than one year and some date to the 1970s.

The Solutions

- Vacate all non-felony warrants that are older than 6 months and all warrants for non-violent felonies that are older than a year. Purge these old warrants from law enforcement databases.

- Conduct a review of more recent warrants and vacate all that are for violations or offenses that would not result in a jail sentence.

- Develop new policies and practices to address traffic and other violations through non-arrestable civil citations instead of warrants.

About

Through awareness, education, advocacy, and litigation, the Fair Fight Initiative empowers, legally defends, and protects those directly affected by our broken criminal legal system with a vision to end mass incarceration and the systemic racism that drives America’s addiction to jails and prisons.

Summary

Baton Rouge has a problem with arrest warrants. Warrants are legal documents that instruct police officers to search for, arrest, and detain someone. If you have a warrant out in your name and a police officer identifies you, you can be arrested and jailed.

Warrants are supposed to help police detain people who are “armed and dangerous”; every person on the FBI’s Most Wanted list, for instance, has a warrant out for their arrest. And, when used appropriately, warrants have proved to be useful in finding the very small number of people who actively threaten public safety.

But that’s not how warrants function in Baton Rouge. Due to warrants alone, police and sheriff’s deputies may immediately jail more than 40,000 people. Here, 12 percent of the adult population has a warrant out for their arrest. That means that nearly one in three households contains someone who has a warrant out for their arrest. If no one in your household has a warrant out in their name, odds are that someone who lives next door to you does.

The warrant rate in Baton Rouge is almost 15 times the national average. If the parish’s household income rather than its warrant rate were 15 times the national median, the typical household in Baton Rouge would earn a million dollars a year in income.

The warrant rate is even higher for Black people in Baton Rouge. Black adults are 2.4 times more likely than white adults to have a warrant for their arrest. Baton Rouge’s warrant problem exacerbates the situation at the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison (“jail”), where at least 48 people have died since 2012.

The Per Capita Warrant Rate In Baton Rouge Is 14.6 Times The National Average

Warrants appear to be a significant contributor to the parish’s jail population. Changes to warrant practices promise to reduce the jail’s population and improve safety in the jail.

The dangers of Baton Rouge’s warrant problem are unwarranted and unnecessary. 98.8 percent of warrants are for something other than a violent felony, and 89 percent of warrants are more than a year old, with some dating back to the 1970s. The vast majority of warrants are for minor violations that would result in a fine, not an arrest or a jail sentence. Parish law enforcement has issued almost 14,000 warrants for traffic violations that are less serious than speeding.

Do we want a system that puts citizens and police in dangerous and confrontational situations because someone drove with a broken taillight years or even decades ago? Do we want our neighbors in jail because they forgot to renew their license on time? Do we want to continue to spend millions each year on a system that just makes life in Baton Rouge worse?

Recommendations

These recommendations promise to greatly reduce the number of people in Baton Rouge with an active warrant. Doing so will not only reduce tension and improve relationships between the parish’s population and its police, it will also allow police to focus their resources on the small number of warrants that relate to dangerous crimes.

Policymakers in Baton Rouge can Address the parish’s warrant crisis and improve public safety at the same time.

This report recommends that Baton Rouge immediately:

1. Vacate all non-felony warrants that are older than 6 months, all warrants for non-violent felonies that are older than a year and purge them from law enforcement databases;

2. Conduct a review of more recent warrants and vacate all that are for violations or offenses that would not result in a jail sentence;

3. Develop new policies and practices to address traffic and other violations through non-arrestable civil citations instead of warrants.

Background

Baton Rouge is considering spending millions of dollars on a new jail that is much bigger and more expensive than necessary. The existing jail currently confines approximately 1,000 people, with another 200 or so housed in other parish detention centers. Experts retained by the Baton Rouge Area Foundation (“BRAF”) estimate that a new jail with 1,360 beds would be needed if no reforms were taken within Baton Rouge’s criminal legal system. The most recent proposal by Sheriff Sid J. Gautreaux III proposed building a new facility capable of incarcerating 2,500 people.

The authors of this report acknowledge that a new jail is necessary. The current facility is dangerous and deadly. At least 48 people have died in the jail since 2012. The facility’s death rate is nearly four times the national average. A national corrections expert who recently inspected the jail reported that “every aspect of the jail … ranged from inadequate to deplorable.” Any new facility, however, must be significantly smaller than BRAF and the Sheriff’s proposals.

Methodology

The Fair Fight Initiative conducted this investigation of warrant practices in an attempt to identify ways that Baton Rouge could safely reduce its jail population. Fair Fight researchers built a web-scraping tool that consolidated case-level data made public by the East Baton Rouge Sheriff’s Department, then analyzed this data to arrive at the findings presented here. The data covers all active warrant cases in November 2020. In cases where multiple offenses were associated with a single warrant, only the most serious offense is reported.

Smaller jails are safer jails.

Smaller jails enable closer supervision of both Staff and detainees, and they mitigate stressors associated with the “churn” of jail populations.

A smaller facility is especially important in Baton Rouge given the parish’s history of medical neglect, use of force, and violence within its jails.

Findings and Data

Warrants are a problem for all residents in Baton Rouge, but they are particularly so for Black people. Black adults in Baton Rouge are 20 times more likely than the typical American to have an active warrant. White adults in Baton Rouge, meanwhile, are 8 times more likely than the typical American to have an active warrant.

Warrants are a problem for all residents in Baton Rouge, but they are particularly so for Black people. Black adults in Baton Rouge are 20 times more likely than the typical American to have an active warrant. White adults in Baton Rouge, meanwhile, are 8 times more likely than the typical American to have an active warrant.

Violent felonies make up just 1.2 percent of all active warrants. Ninety-nine percent of active warrants are for violations that are not violent felonies. Well over half (60 percent) of all active warrants are for traffic violations.

Violent felonies make up just 1.2 percent of all active warrants. Ninety-nine percent of active warrants are for violations that are not violent felonies. Well over half (60 percent) of all active warrants are for traffic violations.

Even warrants for traffic violations are not for dangerous behavior. Almost 14,000 active traffic warrants are for violations that are less serious than speeding. Minor regulatory violations account for more than 25 percent of all active warrants in Baton Rouge.

Even warrants for traffic violations are not for dangerous behavior. Almost 14,000 active traffic warrants are for violations that are less serious than speeding. Minor regulatory violations account for more than 25 percent of all active warrants in Baton Rouge.

The age of an active warrant is an indication of how serious law enforcement considers it to be and reflects law enforcement’s priorities. Active warrants in Baton Rouge are astonishingly old: 89 percent of all warrants are older than one year old, and nearly half (46 percent) are older than five years old. The oldest warrants in the database date to the 1970s.

The age of an active warrant is an indication of how serious law enforcement considers it to be and reflects law enforcement’s priorities. Active warrants in Baton Rouge are astonishingly old: 89 percent of all warrants are older than one year old, and nearly half (46 percent) are older than five years old. The oldest warrants in the database date to the 1970s.

If Baton Rouge purged all warrants older than six months old, its per capita warrant rate would still be higher than the national average.

Conclusions

Ramifications For Public Safety

The warrant problem in Baton Rouge makes all of us less safe. More than 40,000 people are vulnerable to immediate arrest and jailing. In addition to contributing to problems at the jail, this introduces incredible tension and danger into every contact police make with citizens. Because the stakes of every police interaction are so high – an arrest can jeopardize not just your freedom, but also your job, your custody of your children, your ability to pay rent, and more – interactions are needlessly dangerous. When people are scared for their lives and freedom, they are more likely to run or resist, putting themselves, bystanders, and police and sheriff’s deputies in danger.

The vast majority of warrants are for non-serious offenses. Nearly 99 percent of warrants are for something other than a violent felony, and 60 percent are for traffic offenses. The age of active warrants in Baton Rouge is further testament to the fact that they are not a law enforcement priority: 89 percent of warrants are older than one year old.

Baton Rouge Should:

- Vacate all non-felony warrants that are older than 6 months, all warrants for non-violent felonies that are older than a year and purge them from law enforcement databases;

- Conduct a review of more recent warrants and vacate all that are for violations or offenses that would not result in a jail sentence;

- Develop new policies and practices to address traffic and other violations through non-arrestable civil citations instead of warrants.

Baton Rouge can reform its warrant practices, improve the safety of law enforcement officers and the public, and save tens of millions of dollars by avoiding building a large, expensive, and less safe jail.

Acknowledgements

Fair Fight Initiative thanks Klara Drees-Gross, Katherine Taylor Kerr, and Cyrus O’Brien for their contributions to this publication.

Featured in The Media