Interview With Max Rose

Dave Kartunen:

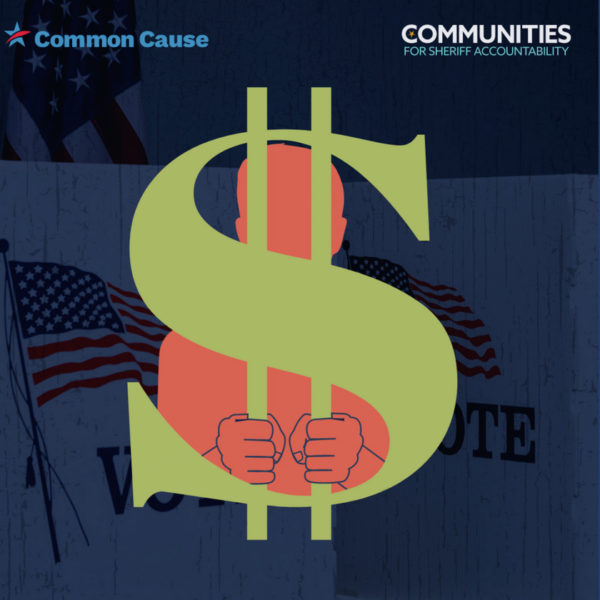

Our guest in this episode of the Fair Fight Initiative Podcast is Max Rose, the founder and executive director of Sheriffs for Trusting Communities. And who with Linda, is part of another organization called Communities for Sheriffs Accountability, who just released a fascinating study about the nexus of profit and warehousing people, and sitting at the center of that are our sheriffs.

Linda:

Well, good morning, Max Rose. Thank you so much for sharing your time and your experience with our podcast listeners, and I take it very personally that you are here. You are one of my most favorite people in the whole wide world. And as I’ve been doing this work, it’s been so funny how instantly God has allowed me to connect with someone on a soul level. And you’re just one of those people, whether you feel the same way about me or not.

Linda:

The work that I have been involved in with you has enriched my walk as an organizer, has empowered me as a person, and has really helped me heal through a very hard time. And I don’t think you know that. The platform that you and the amazing people that work with you at C for SA is just galvanizing. And I can’t wait for our listeners to hear all about what’s going on, what’s on the horizon, and as we like to put it in C for lingo, you know what we’re throwing down on together out here in these streets. So again, welcome, welcome, welcome. And I’m going to introduce you to my partner. I’m not going to say partner crime-

Dave Kartunen:

Don’t say crime.

Linda:

Partner in justice here, Mr. Dave Kartunen.

Dave Kartunen:

And we got a guest that we can start with news. I mean, Max, you’re making news. So tell us about the paid jailer.

Max Rose:

Yeah, I will. I will also just say to Ms. Linda, since it’s just the two of us here, that it is mutual. And in addition to everything you just named, I consider you one of my personal heroes and your vision and your courage and your bravery is a central reason why I do this work, and I feel incredibly lucky to do it alongside you and so many other folks day-to-day.

Linda:

Thank you.

Max Rose:

I couldn’t let that go without acknowledging and naming.

Linda:

Thank you, Max.

Max Rose:

How much I love you Ms. Linda.

Linda:

I love you too, darling.

Max Rose:

But Dave, to your question, the paid jailer report out on Wednesday, excuse me, out on Tuesday, shows a system in which sheriffs are receiving campaign contributions and in return they’re building new jails, they’re granting healthcare contracts, they’re selling commissary contracts, they’re issuing more concealed carry permits, and there’re real consequences in people’s lives. It leads to sub care healthcare and folks dying behind bars. It leads to jails that shouldn’t be constructed being built day to day.

Max Rose:

And it’s a system that really begs the question, whether sheriffs are making decisions based on our safety and what our community needs, or whether they’re making their decisions based on the highest bidder. And it shows roughly $6 million across just over 40 sheriffs offices across the country. So just the tip of the iceberg. It shows that this is ubiquitous, that this is a centrally run system. And it also just makes the case that if we even want a chance at a fair justice system and in making sure sheriffs are doing their jobs, we’ve got to get this paid jailer. We’ve got to get this money out the system.

Dave Kartunen:

Yeah, it’s a form of legalized corruption, I think is the best term that you can slap on it. And to say that it’s just 40 sheriffs offices, I mean, you talk about a state where sheriffs are the most powerful political figure in their community. Georgia has 159 counties on its own. That’s 159 sheriffs just in one state. And I think I’d like you to, for either the passive listener or for the very engaged listener who understands what a sort of insidious arrangement this is, is to take one example, whether it’s commissary or phone calls or healthcare, and break down the pay for play arrangement that creates this form of legalized corruption, where the only way to make it profitable is to continue to deliver inputs. And I say inputs very clinically there, because this system relies on largely poor black and brown people to be inputted into the system to continue the profit model to run.

Max Rose:

Yeah. So most of you all’s listeners will know that sheriffs control roughly 80% of the jails in the country. And those jails almost entirely are actually publicly run. We think of private prisons. There aren’t many private jails. But where the private sector has an interest in jails is in millions and in some places tens of millions of dollars of contracts that have a real impact on the day to day lives of incarcerated people. And probably the most covered and the kind of contract that appears most clearly throughout this report is with healthcare vendor.

Max Rose:

So take the case of Massachusetts and Thomas Hodgson, the Bristol county sheriff in Massachusetts, but this is also true with sheriffs in Louisiana, and we can get to that in a second as well. CPS Health Care is the healthcare provider to the Bristol county correctional facility. Thomas Hodgson has received more than $12,000 in donations from CPS. We know nothing about the outcomes for CPS. We don’t know whether people who come into Bristol county and are incarcerated turn out with better healthcare outcomes. We don’t know about if you have a substance use issue, whether they’re fixing that in jail. All we know is there’s a major contract going to a big campaign donor to Thomas Hodgson.

Max Rose:

And in that jail, dozens of folks are dying. Some by suicide, some by overdose, with zero consequences, zero independent investigation, and zero transparency to what the role of CPS Health Care is and isn’t in that system. And CPS we saw throughout the sheriffs in Massachusetts, but you can insert a different healthcare company in a different place. Ms. Linda, remind me the healthcare company in East Baton Rouge.

Linda:

CorrectHealth.

Max Rose:

CorrectHealth

Linda:

CorrectHealth, yeah. And in Georgia as well.

Dave Kartunen:

Corizon too.

Max Rose:

Yeah. CorrectHealth in the East Baton Rouge sheriff’s office, has put substantial resources into that sheriff’s office. And we know quite well the results in East Baton Rouge.

Linda:

Most definitely. I will say that, when I became affiliated with the organization of Sheriffs for Trusting Communities, and subsequently the Communities for Sheriffs Accountability, just the meticulousness of what we knew, the comprehensive way that it had to be approached, but the money was always the backdrop, right? We knew that coming in. But the educational implications of this report, this paid jailer report.

Linda:

We just had an opportunity on yesterday. There is a group out of Houston who is fighting because they have pretrial people that are being transported into a private correctional facility. But we were in real time able to maybe give them a strategy of there’s this resource out there, this paid jailer report that has come out, and you may find that your sheriff has a tie to this particular facility. So can you speak on the fact that as you were formulating, and even coming up with a concept of doing this campaign, this analysis, what you felt it could be as a resource to people who are looking to really delve into the power that is levied by the sheriffs in these communities.

Max Rose:

I’m so glad to hear, Ms. Linda, that it’s been useful. And I think the actually origin, and I don’t think I’ve told you this, may have been in our work with you all in East Baton Rouge. Because in this report, you’ll see several references to Sid Gautreaux, the sheriff there. One of the worst offenders in the country. And Ms. Linda, you and Reverend Anderson and Michael and others, had been pointing out these contracts and how corrupt they were and how poorly executed they were and how it had real consequences in people’s lives. And then it was also almost impossible to tell who the sheriff contracted with because it wasn’t open and it wasn’t public, and certainly hard to compare the donations to the sheriff with those contracts.

Max Rose:

I mean, I think the origin of this was working with organizers like you all. And seeing that this was ubiquitous, that if we wanted a system based on safety, money in sheriff elections from private interests cut across every community, and that we needed to call that out, we needed to take that money out of the system. And we need to do that in part so that advocates can make a case that’s based on justice.

Linda:

Yeah.

Dave Kartunen:

You live this work, but when you compiled it, was there anything that surprised you?

Max Rose:

I don’t think we’ve had a single sheriff in here that we examined where we didn’t find a potential conflict, and that might have been the biggest surprise. And that shouldn’t be a surprise. The institution of sheriff is pretty rotten. I like to quote James Baldwin saying, “The Republic hired the sheriff to keep the Republic white, to keep it free of sin.” And the sheriff fundamentally has done that job for as long as it’s been in existence through convict leasing and through racial terror lynchings and through their role in deportations today.

Max Rose:

And what that means is that the system has developed in a way that is pretty consistent across the country. They play very different roles in different parts of the country, but what is consistent is that the sheriff is really central to over policing, over incarcerating communities of color. And that they’re motivated by in part these private sector companies. So I think the ubiquity is one thing that surprised me.

Max Rose:

I think the second thing that really surprised me was the range of companies we find in here. Some of it is big national corporations, like the healthcare corporations that we just named. Some of it is the gun range down the street that has a real interest in a sheriff issuing more concealed carry permits, so people can carry more weapons, so they’ll be able to practice more at the gun range. Some of it is energy companies who want sheriffs to protect their land from first amendment protestors. It is big companies, it is small companies, and it is in almost every single industry that has a financial interest in sheriff’s office.

Linda:

Yeah.

Dave Kartunen:

Having been impacted in my reporting career by these practices, I was not the sort of casual reader of this and even recognized the names in Bristol county, which is one county away from where I live, and Johnny Wilcher in the county I used to report on. But I think the part that kind of sunk home for me was that it was everywhere. It wasn’t just in Southern communities, it’s in New England communities, it’s in California. And you talked about how the model has been set up the same everywhere.

Dave Kartunen:

However, what I don’t think people grasp is that because of the way we select our sheriffs, as opposed to the way that we select and certify our police chiefs and our police officers, that you can really distill this down to almost political, I don’t want to say armies, but political security forces. Where their interest is not only serving their donors, but exacerbating issues that call for the need for more security.

Linda:

Right.

Max Rose:

And I think we see that in the proliferation of sheriffs in the anti-vaccine, anti-mask movement, in our anti-democratic movements across the country. And I would say this report and our work doesn’t look too policing as a model of police chiefs and police departments. And it’s important to acknowledge that. That sheriffs present this really unique set of issues that has a lot in common with police chiefs, but what we’re going towards can’t be the kind of policing that was the subject of amazing mobilization around the world after the murder of George Floyd. It’s got to be a more fair, more safe justice system for all of us.

Linda:

Yeah. I know one of the exciting things for me and in the work that I do specifically in Baton Rouge was that, you mentioned George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement and all of this social justice that has pushed forward. And a lot of it was so focused on the police department, right? It was always about the interactions between police officers and citizenry. What my community will tell you is that we’ve always known the power of sheriffs. And I think the man and you had in the conversation, I likened him to the Wizard of Oz. He’s the one behind the curtain that so many people don’t know about. And it was so refreshing and I got so excited to hear that there was this organization that was focusing dead in on communicating to the public just how powerful sheriffs are.

Linda:

So I’m going to shift a little bit from the paid jailer, which a baby of what has been born from your organizations, and I really want you to educate our listeners on just what Sheriffs for Trusting Communities and the C for SA really is all about and how important it is to focus these issues when we’re talking about criminal justice reform.

Max Rose:

Yeah. And I want to just echo something that you just said, Ms. Linda, folks often say, no one knows who the sheriff is. No one knows what the sheriff is. And that’s just not true, if you’ve had a loved one who’s been in jail, if you’ve had a loved one who’s been deported. And if you live in a rural area, it’s not true. There’s a poll that came out of North Carolina that showed that 56% of rural North Carolinians can name their sheriff more than can name their U.S. senator and congressperson. More than can name, this is a North Carolina fact, and anybody who loves college basketball will understand why this is powerful. More people in rural North Carolina can name their sheriff, they can name Mike Krzyzewski and Roy Williams, the coach at Duke and the former coach at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Max Rose:

So the sheriff is incredibly ubiquitous figure in a lot of people’s lives in this country, and so I was not the first to pay attention to the sheriff. There have been generations of organizers. Mostly black and Latino folks and indigenous folks who stood up to convict leasing, who went down to Mississippi to fight sheriffs who were trying to prevent voting. In Florida, Harry T. Moore, one of the first martyrs of the civil rights movement, lost his life going against Willis McCall in a really powerful campaign that’s chronicled in a book by Gilbert King that I’d really recommend to folks.

Max Rose:

So I always try to preface talking about my work, or our work together, Ms. Linda, by saying, I didn’t discover sheriffs. There is a long generation of folks who have been fighting sheriffs. I have the pleasure of working in partnership with a lot of those folks. And I do that through an organization called Sheriffs for Trusting Communities, which supports organizers across the country. And we do three primary things. We help folks understand what sheriffs do and build a different vision for the sheriff. We do a little bit of direct election work, and then we work with partners to hold sheriffs accountable and make sure policies go through that really protect communities.

Max Rose:

And as a part of that work, I’ve had the amazing pleasure of helping to build, with you Ms. Linda and with other organizers around the country, this coalition called Communities for Sheriff Accountability. So I can do the overview of Communities for Sheriff Accountability. Ms. Linda is on the steering committee as our four or five amazing other organizers across the country. And it launched in August 2021 with a really powerful vision that we can build a world that is safe, that doesn’t depend on the sheriff, and where communities take care of each other, and we have a fundamental freedom of movement.

Max Rose:

It launched with the seven powerful policy demands, which you’ll be able to find at sheriffaccountability.org, and all of its work is focused towards that vision towards those demands and towards building a movement of communities who have been affected by the sheriff’s office, who are going to make this happen over the next few decades because this is a long fight.

Linda:

Yes, Max. You did very well.

Dave Kartunen:

I’d like to hear more from you Max about the accountability part. Because when we were talking with David Utter, who’s one of the founders of Fair Fight Initiative and does the legal side of the work, he was talking about the 11th Circuit decision where sheriffs are immune in plaintiffs cases when someone dies in custody. Deaths in custody is something that both Linda and I are very familiar with. And you can’t name a sheriff in a lawsuit like that. You can name your jailer, who is making $19,000 a year and doesn’t have any assets. And it’s not the that you’re seeking jackpot justice and holding someone accountable, but when there aren’t any assets to pay for a lawsuit, there aren’t any lawyers who want to take the case.

Dave Kartunen:

There are obviously elections to hold people accountable, however if you live in a rural North Carolina community that is say 75% white and 25% black, there probably isn’t a whole lot of prospect for progressive change. What do you find are the best most impactful ways in this moment to hold sheriffs accountable?

Max Rose:

Yeah. I mean, Dave, I got to take issue with what example you gave there, but I’d say there’s a lot of rural conservative folks who are fed up with the justice system. And there is a little prospect. Say Thomas Hodgson’s case, where he’s spending millions of dollars of tax payer money and not taking care of community safety. So there’s demand for change in the sheriff in places that we don’t expect there to be demand. But to your point, elections are not the only mechanism for accountability. They’re just one of several tools we can use.

Max Rose:

So I usually talk about four or five tools. Elections, which we’ve already named. Budgets, county commissioners, parish supervisors. Boards of supervisors often have the purse strings, and we’ve got to really better understand where sheriff’s money is going, what it’s going towards, and what kind of outcomes we’re getting as a community for that money.

Max Rose:

Third state policy change. We really have let sheriffs run over our state legislators across the country. We’re still allowing practices like solitary confinement, which folks have compared to torture. We’re still allowing a lot of sheriffs total discretion and cooperating with ICE. So there’s a lot of possibilities for accountability at the state policy level.

Max Rose:

Litigation. But as you’ve named that has some limits, although there’re frontiers still to be deployed. And then the last, which I often think of as the least useful to us because it’s so hard in different places, is that a lot of states are able to remove their sheriff through the governor, through the attorney general or through the prosecutor. And what I always encourage is have a really clear analysis of where you want your community to be. What safety looks like, what are the mechanisms available to you? Because it does differ state by state, although we can help understand mechanisms. And then have a clear analysis of which path is most useful and most possible in your community. Some places it’ll be litigation. Some places it’ll be elections, others budgets, and some in some combinations, excuse me.

Linda:

Yeah. Okay. So back to the paid jailer, because it’s such an amazing tool that is going to help so many communities with just the very things that you just listed. Because I think nine out of 10 of them are wrapped around where is the money coming from? Where is the money going? Because I know here in Baton Rouge, we move the needle a little bit. We’re just simply asking the question, what do you need this tax? So it’s so very important. I want you to speak a little bit about the people and how they went about getting this information. And how people in the communities can help to add to this report. Because there are a lot of people who are doing this work and they’ve got piles and piles of notes and not really understanding what powerful information they have. So speak about the construction of the report, how you guys kind of came together and then how people can link in and even add to make this a more comprehensive report.

Max Rose:

Yeah. Well, this was amazing, amazing research, and I’m glad that I was not the one as much involved in the day-to-day of the research. Because we’ve had these sheriffs offices that are incredibly opaque, sheriffs aren’t required to tell us where tens of millions of dollars go. And it takes arduous public records to get that basic information. Campaign finance, where who gives sheriffs money is a little bit easier to find.

Max Rose:

So what I required was more than a hundred public records requests to sheriffs across the country from John Henry who was working for Common Cause. We got back roughly 48, 47, of those records requests. And then comparing that to campaign finance reports that look really different in different states. Some states make campaign finance reports available at the state level.

Max Rose:

And then the other really important part was testing that data with our community leaders who know this stuff day-to-day. So we had a series of meetings including East Baton Rouge Parish Prison Reform Coalition in Bristol county for correctional justice and chapters of Common Cause and said, here’s what we’re finding, does that resonate? What’s different? What are we missing here about the story we’re telling? And all that led to this report. But John and team at Common Cause did amazing arduous work. And part of what we’ve got to do here is make sure that information is more easily available to the public.

Max Rose:

And so to Ms. Linda’s point, to your point, some of that can be by us and you can sign on at thepaidjailer.org as an organization to find out more about next steps on the data collection. But some of that has to be done at the legislative and county level. We can’t be the ones doing the basic function of holding them accountable for this incredible power that they have. So we will do more data collection. We will put more data out there, and we’ll do that at thepaidjailor.org, and hopefully with folks help who are listening. So we’d love to hear from you. But we’ve got to combine that with this information being accessible to the public from the government.

Dave Kartunen:

Max, I’m afraid to ask, but is there a good example? Is there an example of the sheriff’s office?

Linda:

I know you’re going to cut this out, but when I tell you, you are asking the questions out of my freaking head.

Dave Kartunen:

I’m not going to cut out.

Linda:

This is so spiritual right now for me, Max.

Dave Kartunen:

Why would I cut that? I hold the editing button, Max. So I think Linda is afraid that I’m going to take out all the personality here, but that was good for me Linda. Why would I cut that out?

Max Rose:

I find my rays of light in, for example, the leaders of Communities for Sheriff Accountability. I like to think less about good and bad sheriffs and more about what is our vision for justice and what’s the new role that the sheriff is going to play. And then the good sheriff becomes the sheriff who is following the lead of community in making a system that is smaller and where fewer people are arrested and people aren’t dying in jail and we’re not jails. So there are really good examples of sheriffs who have listened and said the justice system isn’t working.

Max Rose:

The one that I actually like the most is Morris Young in Gadsden county, Florida, who in a conservative rural county right next to Tallahassee has dramatically reduced the number of people he’s sending to state prison. Reduced the size of the jail. Has stopped arresting for basic drug charges and has done so while making the community more safe. Has really demonstrated that this over policing, over incarcerating model isn’t doing anything for our safety.

Max Rose:

And there’re sheriffs who are doing okay work with mental health inside the jail. Who have cut off ICE cooperation or have said they won’t build a new jail. And Susan Hudson in New Orleans is a perfect example of that. [crosstalk 00:28:48] phase three. But I don’t point to one sheriff as the good sheriff. And I also always want to say, when there are sheriffs who are the best in the country, who are making the system smaller, this story is actually still about Harry T Moore after him because they’ve been the one pushing from the beginning.

Linda:

Yeah. Yeah.

Dave Kartunen:

What brought you to this?

Max Rose:

So I come from Durham, North Carolina, which is where I’m sitting now. It’s a city that is mostly black folks and increasingly has a large Latino population. And I’m a white guy who grew up here with every opportunity in the world and who loves a lot of folks who are black and Latinx, who these systems are not working for. So all my work has been at this intersection of folks who I love from home and making the world more fair and just and doing so alongside them. And that’s meant fighting racial, injustice, and economic system.

Max Rose:

And more recently this particular work came because there’s a sheriff in rural North Carolina, just about 20 minutes from here, 30 minutes from here, named Terry Johnson. He was tried alongside Joe Arpaio. That Department of Justice case is how some folks might know his name. But his deputy testified in that case that he would tell them to go get those taco eaters. He stopped Latino drivers at a rate four times higher than white folks that he stopped while he was still the sheriff of Alamance county. And folks in Alamance county who don’t have papers often won’t go outside of the city lines for fear of going in his territory.

Max Rose:

So this started actually just with me and some friends there saying, how do we get rid of this one particularly awful sheriff? And like the rest of this work, there had been more than a decade of deep, brave organizing in Alamance county. And the case of Alamance county is still going on because he’s still the sheriff there. But this one I was so sorry to hear about folks driving you off the road there because in Alamance county, during that department of justice case way before I was involved, he would park his deputies outside of the houses of people organizing. And this process of systematically scaring, intimidating, folks who dare to ask the question is pretty ubiquitous.

Linda:

Yeah. Yeah. I tell you one of the things that I appreciate so much is the affiliation of our Latinx family, our Latino family, in this fight. It opened my eyes a lot, because sometimes when you are being oppressed and targeted, sometimes you only see your experience and you don’t really reference how other people are being impacted. Even white people, even yourself, and I won’t bring you to the story that you told us at the retreat about your friend, and I know that’s very emotional for you. But the many people that I met there and the stories of how their families are being separated. How people are even, like you said, scared to go to the grocery stores, because it so affects the very day-to-day existence that we have. And for these people to have this much power to be able to cause such… I mean, just mental illness, right? Is amazing.

Linda:

And so this fight, we’ve got to always make sure that we’re referencing the totality of the experience of all of our citizens that are caught up in this web. And I think that’s something that the organizations do so well. The diversity that I find in your organizations, the affiliations and just the outreach to even include more because once you get in and start pulling the thread of that sweater, you unravel so much that you already didn’t know was there. I mean, we even got Dave here ready to go pick it outside in Massachusetts, right?

Dave Kartunen:

Yeah. We’ll connect on Bristol county when we’re done. I think Linda’s summation there is a nice way to close this conversation and give you the last word at the same time, Max. And that is around what she just said, that the totality of this, if you live in the United States, you’re touched probably by a sheriff. And in our conversation, you have provided myriad ways where anyone can engage. Whether it’s just going and requesting their own budget or going to their commission meeting or telling their legislator if they have an interpersonal reaction of doing their job at the state level. Whatever that sort of vector of engagement is, if you live in the United States, you’re touched by a sheriff, there’s something you can do. And I want to give you that opportunity to invite people to engage.

Max Rose:

Well, I think the first and foremost place that people can and should plug in is in their local communities. And I think you can go to sheriffaccountability.org and see some of the demands of Communities for Sheriff Accountability and what you could be asking of your sheriff. Schedule a meeting with your sheriff. Understand who’s organizing and asking questions of your sheriff already and go to their meetings, join their project. If you’re with an organization, join Communities for Sheriff Accountability and do so by going to the website sheriffaccountability.org and using the contact link there.

Max Rose:

The biggest ask I have for folks is talk to folks who you know who might not understand the role of the sheriff. Help educate your neighbor about what they can and can’t do, and about their historical role and their actual role. And then help them understand what safety looks like that doesn’t depend on this office. And I think if we have tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, then millions of small conversations in our communities, and really clear demands for our sheriffs and county commissioners and for our state legislators, then we’re going to build an incredibly powerful movement and we’re going to increase the power of an already powerful movement and win this.

Linda:

Well, I tell you’ve done the lion share, and I know you’ve got more to do.

Max Rose:

We’ve got more to do.

Linda:

We’ve got more to do. Yeah. You ain’t getting rid of me, I can tell you that right now. But thank you for this small thing that we can do to add. Thank you for all that you’re doing, but thank you for favoring me with your conversation, with your presence, with your knowledge and with your time, that’s so important. So I love you Max, and thank you so much for being with us today.

Max Rose:

I love you Ms. Linda. Thank you so much for having me on. Great to meet you Dave.

Dave Kartunen:

Max Rose is the founder and executive director of Sheriffs for Trusting Communities. And with Linda, has just released the paid jailer as part of Communities for Sheriff Accountability. You can find both of their websites under links we mentioned at fairfightinitiative.org.

Featured in The Media